|

| by Marsmet via Flickr/CC |

JH: Please join me in welcoming Jordan McCollum to the blog today to chat with us about crafting better character arcs. Characters who grow and change are usually the ones readers remember, and she'll share a few tips on how to get the most out of your arcs.

An award-winning author, Jordan can't resist a story where good defeats evil and true love conquers all. In her day job, she coerces people to do things they don’t want to, elicits information and generally manipulates the people she loves most—she's a mom. Jordan holds a degree in American Studies and Linguistics from Brigham Young University. When she catches a spare minute, her hobbies include reading, knitting and music. She lives with her husband and four children in Utah. She offers free writing guides, including a guide to character arcs, and blogs about writing craft and the creative life at JordanMcCollum.com.

Take it away, Jordan...

Character arcs, or internal character journeys, are integral in fiction. While it might not be strictly necessary in building a book that works, an effective internal journey helps to create fiction that resonates with readers long after the events of the plot are forgotten.

Of course, anything that powerful can be very tricky to execute. These five steps to better character arcs outline the easiest, most basic things you can do to start showing your characters' growth.

1. Show the broken beginning.

Every character, and every character, has to start somewhere. We know that in the ordinary world, something is missing from the protagonist’s life. That doesn’t just mean a love interest or a murderer that needs to be brought to justice—there’s something deeper, on an emotional level, that the character needs.

But you cannot just tell us "HERO HAS THIS PROBLEM." You cannot just have other characters tell us "HERO HAS THIS PROBLEM." We need to see the problem in action to understand the full effect on the character and his/her life. If our hero is looking for stability (slash AFRAID), we need to see that fear dominating his life. Maybe he decides not to do something he really wanted to do because of his fears.

This should be negative—either the character sees it hurting him or we see it as a negative attitude or both—because the character really does need to change (though he won't until external events force him to).

(More on why characters arcs make readers care here)

2. Tailor the antagonist.

For an effective character arc, we need to see the antagonist working against the character's internal journey as well as the external journey (the plot). Just like the broken beginning might not be a conscious problem for the protagonist—they do, after all, cope with whatever their fears or problems are, and they have for a while—the antagonist's internal attack might be under the surface.

My favorite way to do this is to align the antagonist with this fear, this mistaken belief, this problem. If the heroine's weakness is a lack of trust, perhaps the perfect antagonist for her has that same weakness, an inability to trust. In some way, that should be his downfall. Maybe he can't delegate some task to his minions, he has to do it all himself, but he just physically can't.

3. Make REAL choices.

The character will grow as s/he makes choices throughout the story, choosing how to act and react to the external plot events. Alicia Rasley, RITA-award winning author, points out that if the character's choices are too easy, they can't force the necessary growth: "If the choice presented is too stacked in one direction, then it’s not a choice."

A stacked choice is one that any decent human would make. It's not easy to run into a burning building to save a child, but I hope any decent human would at least want to help. Unless your character is journeying from . . . ahem indecency to decency, we need to see the protagonist making choices that are hard for him.

A real choice in our journey of learning to trust others might be as simple as asking for help. A friend offers, but the heroine can't accept help, or is too afraid to share her problems. The good of the world isn't resting on the choice, only the good of the character.

Finally in this area, sometimes the character is going to get it wrong. They've spent significant time—maybe their whole lives—not trusting, living in fear, or whatever your journey may be. It's worked for them. It's been an effective solution to their problems until now. So it's natural for them to try to continue to do that. It's hard to change. Don't make it too easy for your character—give us a reason to root for them!

(More on character arcs and plot here)

4. Use the new strength at the climax.

At the climax, our protagonist and our antagonist reach their final showdown. It's here that we—and the protagonist—see the real cost of fear/belief/problem. When the antagonist can't let go, can't grow, that becomes their weakness.

In our example above, the antagonist has trust issues. So he refuses to let anyone help him, since they won't do it right. He has to do everything himself. But who can manage everything? Who can control everything?

Because of the events of the story, the protagonist has learned and grown. Now s/he is strong enough to defeat the antagonist. Maybe our heroine has learned to trust someone else, and as a team they're able to overwhelm our overstretched antagonist.

At the climax, the character uses and finally proves the lesson they've been learning throughout the story to defeat not only the external antagonist, but their own internal doubts.

(More on guides to crafting inner character arcs here)

5. Show the changed man.

The climax of the story might be the proof for the protagonist that this lesson has been worth it, but we readers often need just a little more help. After the climax, we must show the results of the characters’ final choice, to confirm that change is real and permanent, not just an instant convenience to beat the bad guy at a critical moment.

So in the final moments of the story, look for some little gesture your protagonist can make to show that she's really learned her lesson. Maybe she has the chance to go off on her own to do something she normally would have done alone, but she looks back at her team and nods for them to join her. Show that change has really taken root, and leave your readers happy.

Did I say this was easy? It's not. But character arcs in fiction show the power of transformative experiences. Watching that transformation, rooting for it, and growing with the character are major reasons we read fiction. Aristotle first coined the term catharsis for this experience, any extreme change in emotion that results in renewal and restoration, and it's been a major purpose of fiction for millennia.

And on a more practical level, it also helps to make your story resonate, your characters unforgettable, and your readers even happier.

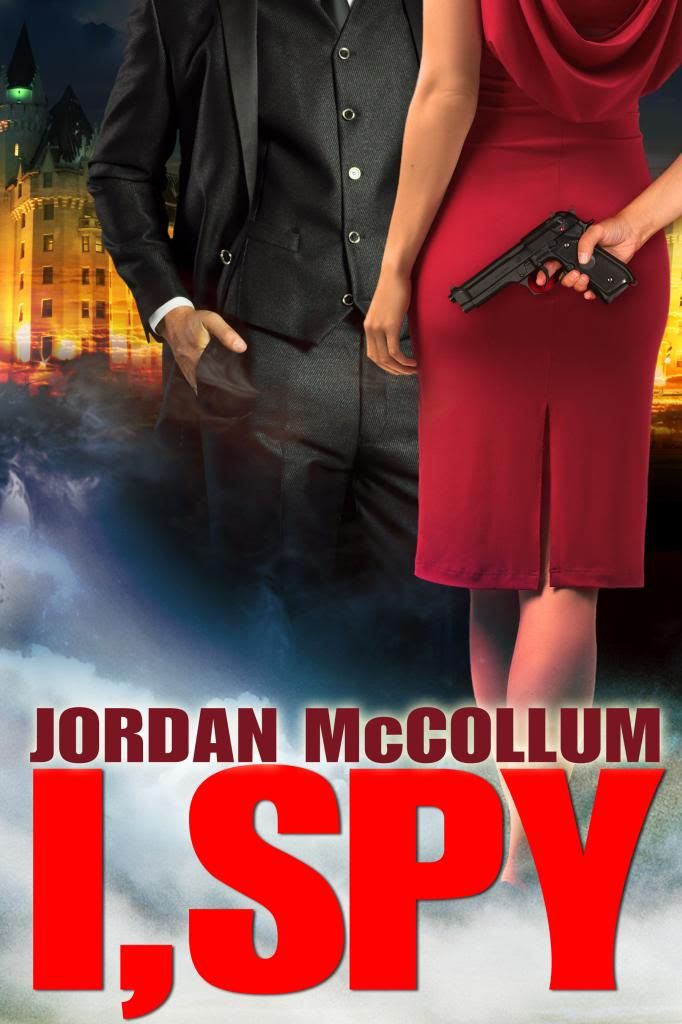

About I, Spy

Jordan's first novel, I, Spy, is out now: Canada's the last place you’d expect an American spy. But even idyllic Ottawa has deadly secrets—and so does CIA operative Talia Reynolds. There's only one thing she can't do: tell her boyfriend Danny about her Top Secret occupation. When her latest target turns around and targets Danny, her schedule isn't the only thing suffering. To save her secrets and her country, Talia must sacrifice the man she loves.

Jordan's first novel, I, Spy, is out now: Canada's the last place you’d expect an American spy. But even idyllic Ottawa has deadly secrets—and so does CIA operative Talia Reynolds. There's only one thing she can't do: tell her boyfriend Danny about her Top Secret occupation. When her latest target turns around and targets Danny, her schedule isn't the only thing suffering. To save her secrets and her country, Talia must sacrifice the man she loves.Facebook | Twitter | Goodreads

More about I, Spy | Amazon Kobo | direct from JordanMcCollum.com.

#2 sounds almost like the antagonist should be a mirror of the protagonist, like Rene Belloq in Raiders of the Lost Ark. Like Indy, he's an archeologist driven to unearth great treasures. But unlike Indy, he doesn't know when treasures should be left alone.

ReplyDeleteI haven't given my antagonist enough thought, but I do believe he would work really well as a mirror image of my hero. Both mistrustful jerks, both determined to hold the upper hand... Thanks!

Great reminders. My favorite is #2 - it is what made me enjoy the Harry Potter series so much. Harry and Voldemort had lived essentially the same lives up to a point. But their later journeys stemmed out of the choices they made, and that's what eventually affected the outcome. I love it when I see this in a book.

ReplyDeleteRachel—I usually stop short of actually using the term "mirror" because you can use the same weakness or mistaken belief applied in very different ways for the protagonist and antagonist. Of course, you can use it in the same way as in Raiders. (Have you ever read the story conference for Raiders? It's got some amazing storytelling advice!)

ReplyDeleteSwati—Oh, yeah, Harry's and Voldemort's journeys are good examples of that mirror structure Rachel mentioned! (There are other ways to do it as well, of course.)

Where her mistrust means she creates and maintains emotional distance, his mistrust means he keeps secrets and undertakes tasks unnecessarily; like that?

ReplyDeleteWhere can I find the story conference? I didn't know such a thing existed!

Yeah, that's a great example.

ReplyDeleteGeorge Lucas, Steven Spielberg and Lawrence Kasdan took a week to muddle through the story for Indiana Jones, and came up with enough material for two movies. I first came across the transcript for the story conference here: http://mysterymanonfilm.blogspot.com/2009/03/raiders-story-conference.html

I think your last point -the one about showing that the change is permanent- is the hardest thing, but also the best as far as making a story memorable. Those moments always give me delicious warm fuzzies.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the post. I will post it on my class wiki and reread all the links. Need this stuff right now for my own WIP!

ReplyDeleteI enjoyed this list – especially point 4. It's that moment where the hero, having gained their hard-won insights, strengths, or knowledge, can apply it, winning the battle and conquering themselves. Thank you for creating a helpful resource.

ReplyDelete